- Home

- Mphuthumi Ntabeni

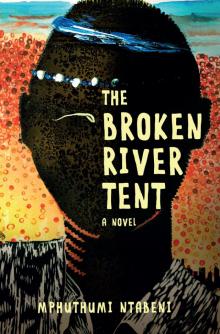

Broken River Tent Page 7

Broken River Tent Read online

Page 7

Phila never loved his father more than when he was a casting silhouette against a gurgling river, even as he later learnt to understand that a river ran through their characters in other things. And, to date, few things excited him as much as the break of what his father called ‘river silence’ with the thrashing of a trophy fish.

Phila drove another hundred kilometres or so to arrive in East London as the shadows were lengthening. The pin-prick of the lighthouse, at the Windmill, where he sat eating fried fish and chips, was barely visible through the low-hanging sky. The grey light intensified the cold wind from the harbour. The area, of course, stirred old memories – some of them kind, some not so pleasant.

When he felt the echo of depression he decided to go to the B&B he was booked into, hoping for a good night’s sleep.

He woke at the first streak of dawn. Memory scars itched. He made himself coffee, which he drank on the balcony. The peace of the morning was distracting. The golden sun on the sea had the effect of amplifying things in his head. His first assignment of the day was hiking the Amathole mountains, where the gourd of iMbokotho broke. He felt the excitement grow with every sip of his coffee. I’m walking in the full daylight of our history, he thought to himself.

He went inside after finishing his coffee. An airline magazine on the coffee table, with a photo of the late Nigerian poet Ken Saro-Wiwa on the cover, caught his attention. He turned to the article but found it to be bland and poorly researched. He remembered when he had heard the news of the poet’s death. It was the first time he and Arunny had sex. He was still in Berlin then, working late with Arunny, who was originally from Cambodia. She had felt like smoking dagga, so she’d asked Phila if he had any. When he said no she was disappointed. To redeem himself, as a darkie, Phila remembered reading from the papers that Görli, the Görlitzer Park in Kreuzberg, was the best place to score. He informed Aru. They got their coats and left. The next thing he knew they were standing at Görlitzer Bahnhof U-Bahn station waiting for a train to her apartment, where they went to have stoned sex. After they laughed off the micro-aggressiveness of Berlin against people of colour – it had taken them an uncharacteristically long time to get their stash at Görli because people kept approaching them, assuming Phila was the drug dealer, or at least Aru’s pimp. “Wie girl?” became their private joke and mating call for the duration of their two-and-a-half-year affair. He’d been smoking out on the balcony that evening when Aru called him inside. She was excitedly pointing at the TV where a visibly angry Mandela was spewing lava against the Nigerian junta who had just executed some political activists, including Saro-Wiwa. The price of serving the truth, Phila had thought to himself. He had always known about the natural contention between news and poetry. To him the duty of poetry was to historicise the news; to refine and define human experience, unlocking the mysteries of the world through a private view. When the poet has done this successfully, that is, mined the aesthetic rigour of history, then it is transformed into culture. But that poets in his era still paid with their lives for doing this came as a shudder-inducing surprise.

Aru was of the New Khmer Architecture school of thought, and had an appreciation of Vann Molyvann. A Bachelardian himself, Phila and Aru had in common their outlook towards organic architecture and the need for a structure to be a poetic emblem of its environment, as opposed to those who thought architecture should stand out of causality. Although they had known each other for at least nine months, that night was the first time they had really talked. They settled quickly with each other like bugs on a rug, perhaps even loved each other a lot. But, despite what the romantics tell you, there are things even love cannot conquer. The irony was that the poetry Aru loved so much was, when he distilled things to their essence, what tore them apart. Phila was unable to break the bond of solidarity between imagination and memory, something otherwise known as nostalgia. It might have been easy for Aru to up and go to Switzerland so that she could learn at the feet of her master where the rulers of Phnom Penh had exiled him. The deeper urge for Phila was homebound. At least she still signed her emails to him: ‘Your Morning Star’.

Helen was almost as devastated as Phila was when Aru left Deutschland. They were already behaving like in-laws and were extremely fond of each other. Helen was Phila’s second mother, the one responsible for his scholarship application to Germany. Phila had first met her when he was nine or ten years old, the day his father took him to the dentist to take out a rotten tooth. They were still a family then but the storms were already gathering, something even his ten-year-old self could not ignore: the constant disappearances of his dad, especially when he was doing night duty; the subsequent shouting from his mom. His father had taken him to an Indian, maybe a Chinese dentist – Phila hadn’t possessed enough sophistication to distinguish between races or ethnic groups then; but remembering the pockmarked face and bulbous nose, he would now bet on Indian. Also, each time the dentist bent to look in his mouth a wave of curry reached his olfactory receptors – two words he learnt from his medical nurse dad that day when he’d tried to explain the sensation. The dentist was the type who kept lollipops for children; firm with instruction and certain in diagnosis. One thing Phila remembered about him was how he did not talk down to him in the manner of many adults.

“I have this needle, which I am going to prick your gums with. It will hurt a little. But that will help you not feel the pain when I take your tooth out. If you don’t move much, I am gonna give you a lollipop.” The instructions were direct and clear. Phila did not make a single move. He had this strange practice of dissociating himself from pain, a trick he first learnt when he kicked his toenail out on a rock when he was playing soccer. Because his mom had told him not to go out he had had to keep mum about the pain. Only the trail of blood on the kitchen floor told him out. His mom cleaned and bandaged the wound with a promise that it would heal soon enough.

Another time Phila broke his arm at school while playing rugby, but he didn’t know it was broken until the doctor confirmed it. In the morning, when he could not lift his spoon to eat his porridge his mom knew something was amiss. The pain that had kept him awake almost all night had already disappeared by then, but his parents insisted on taking him to the doctor anyway. Phila came back the proud owner of a cast, making him the envy of his coevals at school.

By the time he visited the dentist he had already mastered the art of dissociating himself from pain. The dentist and his dad must have been friends, because they had chatted a lot about different things, mostly tennis. People said things about his father like: “Had it not been for apartheid, your dad would have gone professional.” They meant it as a compliment, but Phila, who was not too shabby at tennis himself, always felt it as judgement of his abilities, meaning that, even though in his era they had more opportunities, it was Phila who was falling short. Phila’s dad found his voice among strangers, which seemed strange to those who knew him to be taciturn within the family. It was a strange thing to observe a different side of his dad when they were out. At home he seemed to assume that the family could read his mind, barking angrily when they got things wrong.

Phila’s English then was still faltering, but he got the gist of his father and the dentist’s conversation about “a puppy for my boy”. That part he definitely got because he had been dying to have a hunting dog like everybody else his age in the village. Being his father’s son, taciturnity and all, Phila didn’t mention anything to his father about the dog, waiting for him to introduce the topic or produce the surprise. He got concerned as the day matured, with his father not mentioning anything while running errands for the general dealership he owned in the village. They went last to the wholesaler, Metro, for shop supplies. Coming out of the wholesaler’s his father said they needed to go somewhere to collect his present – “because you were a good boy at the dentist”. When they climbed the bridge over the railway line, Phila knew they were going where white people lived and instinctively also knew it would not be a pleasant e

xperience if the police found them there.

He was not exactly sure about the details of why they were not supposed to be there, just that it was the apartheid thing everyone talked about all the time. When they stopped at one of the houses with whitewashed walls, picket fence, manicured lawn and military-haircut-style hedge, his father told him to remain in the car while he went inside. Phila knew they were on a surreptitious and risky mission, so he started spying for signs of danger, staying alert. All approaching cars were a source of anxiety, especially police vans. But the only sense of danger, as Phila waited for his father in the car, came with the refuse truck. He was confused as to what to make of it. In the township where he stayed there was no collection of refuse and such – hence rubbish was strewn everywhere or else burnt. Blacks then didn’t have much refuse to dispose of anyway because they lived poor, from hand to mouth. The truck interrupted Phila’s admiration of the white people’s streets, how open and clean they were; neat and orderly compared to those of blacks, who lived on crowded dirty streets, with sewerage permanently leaking from public toilets. White people’s houses had clean white walls, well-groomed lawns and manicured gardens. Black people’s houses were mostly just mud dongas. Later on when he read Orwell in Down and Out in Paris and London, what he described as ‘leprous houses, lurching towards one another in queer attitudes, as though they had all been frozen in the act of collapse’, Phila felt Orwell was defining their township. Strange to Phila also was the fact that there was no one walking drunk on the streets, or women shouting or laughing at each other walking with buckets of water and bundles of laundry on their heads, ambling towards the communal public lavatory, the only place that had running water. These things he associated with the superiority of white people, without understanding why.

Just when he was starting to panic about the truck coming closer to the house his father came out laughing, followed by a white woman. The white woman came to greet Phila in the car, continuing the strange thing of talking to him like an adult, spoiling it only by pulling his cheeks after handing him a puppy.

“Happy, are we now? We have a new puppy! You must take care of it. Feed and clean up after it,” the woman declared. She had ginger hair and pale legs. Her eyes, the colour of a tumultuous sea, were trained on Phila, who acted bluff for fear of embarrassing himself in front of a white, though he was dying to scream with joy. His dad looked as though he had been playing tennis, sweaty as a racehorse.

The first thing that struck Phila about the puppy was its humbug round eyes. She, the puppy, looked at him more with confusion than curiosity. As they drove off Phila was in a fierce burst of happiness.

“Isn’t Helen nice?” His father, too, was now on this thing of treating him like an adult, asking for his opinions and all. Phila nodded his head while concentrating on the puppy, which was trying to chew his finger with its tiny teeth.

It took Phila more than thirty years to piece the puzzle together. All those times when she made him juice during tennis matches at the psychiatric hospital they all worked at, the scales did not fall. Or when they met her in town, or how, when Phila was wearing the Christmas navy suit his dad had ‘bought’ him, she handed him a ten rand note after talking at length with his father. Or when he went looking for his father at the hospital kitchen she came out of the room adjusting her skirts, and his father came out tucking his shirt into his trousers, both of them out of breath. Nothing about these encounters seemed odd to Phila’s mind at the time. People were always out of breath after playing tennis. Helen was just a kind white woman, with a strange accent, who used to be married to an Indian dentist his dad played tennis with. Only after Helen collected him at Frankfurt airport, twenty years later, did Phila finally connect the dots.

On their drive home to the township Phila fought the butterflies in his stomach each time the car looped the bridge. His father, now and then, looked with pride at Phila and the puppy, a match made in heaven, if ever there was any.

After a while he said, in a stern voice, “Know that this dog is your responsibility. You must look after her, make sure she eats and she will be your friend for life.”

Phila ran his hands over the puppy’s soft black fur, studying its face. The puppy was eager as mustard for play, whining a bit, and gently forcing its nose into his fingers when he stopped his playful hand gestures. His father said they must name it Baby – he was always naming things endearing to him Baby. So Baby it was.

They drove a short distance before his father stopped at the fish shop, as was the norm when they went home after a town visit. Phila was left in the car with the puppy, its heart pumping against his ribs like a caged bird. He dared not disturb its sleep by changing positions though he felt a cramp developing in his left thigh.

Coming back, his father embarked upon a lecture about German Shepherds. “… one of the most intelligent dogs on earth. They are very loving and highly protective of their owners …”

And so it proved to be later. Phila’s solar plexus contracted as they reached the apex of the climb of the motorway bridge under which the trains passed whistling to Johannesburg.

When they arrived home the puppy became apprehensive about the strange surroundings. Phila became the object of its trust, being the only thing vaguely familiar to it now amid the cackle of chickens, the mooing of cows, the cavorting of calves, the snorting of pigs and barking of alien dogs. She sniffed the warmth of his arm and buried her head under it. With that Phila’s purpose in life was defined. When Phila was at school, his mother said, the dog spent the whole day in a bad mood, snarling and yelping at those she did not know, with inconsolable whimpers and whines.

But Baby was rubbish at hunting when she got older. True, she made up for it twice over with her sunny personality, more human than dog. The hunter instinct was completely dormant in her. Once while hunting they fell on a warren. Phila rubbed Baby’s nose in the rabbit urine and pellets, then signalled her to go hunt. Promisingly, she did. When the rabbit jumped Baby was so startled she turned around and ran towards Phila. That sealed her hunting fate. Nobody was interested in teaching her the skill after that. It puzzled him, though, because she was an extremely intelligent dog, even if a lazy runner. Whenever Phila pointed her towards the hopping and scampering rabbits, or impala, intending for her to follow, she would look at him quizzically: are you crazy? Or she would just turn her back on the prey and begin a wolf howl. In the eyes of the community she was a failure, a glorified pet. And she was a rubbish guard dog too, only interested in sharing Phila’s bed. She had about her a human poise and dignity; she refused to slap and snap at food with other dogs, so you had to give her an individual dish.

To protect her Phila stopped going to amalima – hunting parties. They took to going on solitary mountain climbing expeditions together instead, which Baby relished, because it meant Phila’s attention was on her. She was good in the quick identification of snakes – just about the only thing she was good at with all that intelligence. Phila loved her to distraction anyway.

Kuyaliwa Ekhaya

A SHARP SQUALL SUDDENLY SPURTED heavy, violent rain, accompanied by thunder, when Phila reached the foot of the Amathole mountains where his hike was to begin. He waited it out inside the car, lit a cigarette, and watched shafts of sunlight struggling to break through grey clouds. There was a fierce intenseness in the air.

‘The problem was the internecine struggles between our different tribes.’

Maqoma was back, sitting in the passenger seat and smoking a pipe that smelled like burning grass.

‘Most interesting to me,’ he continued, ‘were the happenings of fate, the fact that the Mfengus, from the east, and the whites, from the west, arrived at just about the same time in our area. Your ancient Roman friend saw fate as an unchanging plan in the mind of God, who was immutable, and governed everything. Who can argue with that? The Mfengus would have remained our vassals in perpetuity without the arrival of white people who armed them to fight. Perhaps in the end the Brit

ish, with their never-ending supply of redcoats, would have eventually prevailed over us, but it would have taken much longer without the helping hand of the Mfengus and the KhoiKhoi people, and they would have suffered very long and deeply for it. The question I discovered late, after my body had been the property of maggots, is why fate, after building us, would want to break us up into pieces.’

‘Are you trying to say it was the plan of God that the Xhosas lost their land to the Mfengus and the whites?’ Phila asked.

‘I’m saying the plan of God, as Ntsikana saw it, and I discovered late, was that nations must mix. That they clash in doing so is in the nature of things, because of human intransigence.’

‘So it is the inspired ecleticism you like in Boethius? I was wondering.’

Broken River Tent

Broken River Tent