- Home

- Mphuthumi Ntabeni

Broken River Tent Page 4

Broken River Tent Read online

Page 4

“Just promise you’ll try.”

Nandi handed him a cup of rooibos tea. She sat down on the sofa and rested her head on his crotch. “If you decide to leave tomorrow, at least have the decency to say goodbye before you go. I can’t stomach another of your disappearing acts.” She spoke with force of feeling but kindness of tone.

“Perhaps I would like to stay?” Phila rested his arm on the shoulder of the sofa and clasped his chin. “Would there be a room for me?”

“Ja, right! I’m not hedging my bets on that.”

Nandi knew Phila; she knew that he was a man who sometimes unwilled what he willed because of second, third or fourth thoughts.

“When I go, if I go, it’ll be for the last time. Will you wait for me?”

“That’ll be waiting for the coming of Nxele!”

“Come on. It’s only been two centuries. The Christians have been waiting for their Messiah beyond two millennia now. And the Jews have been waiting forever.”

“I’m not religious.”

The music tempered the silence.

“Nandi?”

“Mhm?”

“Do you think when I come back we could, perhaps, live together or something?”

“What are you asking?”

“Only what is in my heart.”

“When you get back, if you still feel the same, we’ll discuss it. But I must warn you, there’ll be conditions, expectations.”

“I’ve been living without conditions for far too long. Perhaps it’s time I learn to fulfil some expectations.”

“Why now?”

“I’ve grown to believe the end of my journey is with you.” Phila decided to grasp the nettle by swinging a blunt axe. “What about your professor?”

“What about him?” Nandi raised her head to meet Phila’s gaze, which refused to meet hers. She continued without guilt. “It would have been nicer had you said you loved me. I guess you’re right not to promise things you don’t feel. Things have to be better than that between us.”

Phila found himself awake at 3:40am. He lay for a while in the dark, listening to the morning sounds. Dawn was at the stage when darkness seemed to illuminate light. A distant rumble of a car engine approached in strain, climbing the steep hill before slowly fading as the headlights moved across the room, leaving behind a convergence of alienation and melancholia. Stasis. Sich verfahren. Losing his head to where, he wondered.

Beside him Nandi was snoring and emitting heat and occasional hypnic jerks. Something he had read somewhere came to mind, about the fundamental teachings of Mahayana Buddhism, the kshanti paramita, which is the capacity to receive, bear and transform the pain inflicted on you by your enemies; also by those who love you. The description seemed to fit Nandi. He had lost count of how many times he had left her for other women. He felt an urgent need to know if Nandi practised Buddhism, as if the answer to that question would collapse the gap between the experienced and the read. He elbowed her, lightly first, then a little harder the second time.

“Hmm … What is it?”

He could see through the light from the street that her eyes were still closed. He elbowed her lightly again. “Are you Buddhist?”

“Huh? Phila, please, it’s late.” She turned towards the wall.

“Actually it’s early. Tell me – are you Buddhist?”

“Phila, I have class tomorrow. What’s this all about?” She turned back again, opening her eyes, allowing them to adjust as she looked for Phila’s face. Confused, she asked again, “What’s this all about?”

“Please answer the question.”

“No. You know I’m Christian, at least nominally. What’s this all about?” she asked, rubbing her eyes.

“I dreamt of Buddha, and am not sure what he wants, if he even wants anything.”

She raised her head, considered his statement for a while, then answered in a throaty, sleepy voice. “Perhaps you’re looking for a religion without God. Isn’t that what Buddhism is?” She punched her pillow before resting her head back on it.

“I never thought of it that way.”

Could it be, having grown under the shadow of the church, thought Phila, I now am longing for the comforts of religion without the constraints of having to pledge my allegiance to a deity? The only thing to really attract Phila in the Christian religion was the commendable life of Christ. As for the other mumbo-jumbo, beyond the records of how Christ wanted us to behave, as written by his disciples and interpreted by the church, Phila had reservations, sometimes even irritations. But he didn’t think the whole thing was as shabby as the likes of Voltaire or Dawkins made it to be. He was just as much not interested in their egos and satanic pride as the mumbo-jumbo they claimed to dispel. I’ll not serve! Most learned people were anti-authority, he knew that, which was why non-belief was more attractive to them. What’s wrong with authority if it is not authoritarian? He often asked himself that question. But now, thanks to Nandi, he was discovering that he also had nostalgia for sanctity.

Nandi had fallen asleep again, which irritated Phila. He elbowed her again, this time more sternly than before, but she turned with a groan and went back to sleep. Questions went through his insomniac mind as he lay supine in bed watching the dull winter-dawn light announce itself through the window. Why would I want a religion without God? What would be the point of that? To appease my vanity? The ceiling was turning from grey to white as he went on with his thoughts for over an hour and a half until he was distracted by Nandi climbing on top of him. Is Christianity morally too demanding, he asked himself, fiddling with Nandi’s breast. The touch of her aureoles quickly aroused him as usual. They made love. He felt needed and lost his thoughts. Nandi came with exquisite grace and a hint of derision in her face before dropping to the side, heaving. She always looked extremely vulnerable after lovemaking, which made her more beautiful in Phila’s eyes.

“That’s what I call a morning glory!” she softly exclaimed.

Phila’s hyperactive mind couldn’t rest. It travelled to a documentary he’d watched once, about the matrifocal culture of the Mosuo people. Apparently, high in the Himalayas in a remote corner of China an agrarian group of people still lived, who had survived for almost two millennia. What fascinated the documentary makers about this culture was the practice of what was termed ‘walking marriage’. In walking marriages a woman does not take a husband. Once she turns thirteen she is given her own bedroom, a ‘flower chamber’ in literal translation, the translator emphasised. She could invite any man into her flower chamber to spend a night with her, so long as he left before dawn. In practice, strangely enough, perhaps even disappointingly to the modern (read Western) world, this usually didn’t result in wild promiscuity. It was more like serial monogamy. The woman, even when she fell pregnant, did not expect or require support from the man. Everything was kept strictly private and separate from the daily workings of the family, of whom she was a part, and to the support of which she made her contribution. Family responsibilities, values and bonds were derived from the family she was born into; male members were expected to behave not only as male figures of the community, but fathers to her children.

With the radical decline in matrimony, and increase in single mothers in black families, Phila thought his people were closer to Mosuo culture than Western, which judged his culture harshly in things like polygamy.

“Nandi.”

“Mhmm.” She was drifting back to sleep again, sex, as always, being her berceuse.

“I think I’m losing my mind.”

No answer. Then, “Can’t you lose it in the morning, when we are all awake?” When he did not answer Nandi raised her head.

“What can be done?”

“I wish I knew. I wish I knew.”

Phila lay with his hands behind his head on the pillow, thinking about Maqoma. “After my father’s funeral,” he said, “I want to visit some places around King William’s Town and East London. Perhaps I see you after?”

“I s

hall be here.”

The declaration felt more like an accusation than assurance to Phila. Shafts of daylight stabbed Phila’s eyes from between the curtains. Nandi got up to go to the bathroom. Feeling in between worlds and modes of consciousness, Phila got out of bed and followed her. For whatever reason, seeing Nandi brushing her teeth at the sink with her underwear hanging on the bathroom rail heightened Phila’s concerns into a panic.

Homewards, towards Selbstfindung, still sich verfahren.

He went to the lounge and turned on the TV while Nandi stepped into the shower cubicle. Afterwards, when she passed through the lounge to go and get dressed, wrapped in a white cotton towel, she asked what he was watching.

“Some professor of psychology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem is convinced that Moses was on psychedelic drugs when he thought he was talking to God on Mount Sinai through the burning bush. I find that interesting.”

“I never heard that before,” Nandi said, going to her bedroom.

Phila went and stood in the doorway. “He says that’s the reason Moses saw stuff other people around him didn’t see.”

“Because Moses was on drugs? I guess it’s plausible – if there’s any proof.”

“The professor thought it was a psychotropic plant. Similar results can be obtained from a concoction made from the bark of the acacia tree, he said. Apparently that concoction is constantly mentioned in the Bible.”

“You’re too absorbed in yourself, if you want my honest opinion.”

“There’s hardly anything religious about it, if you mean to insinuate.”

Phila felt hurt as he stripped to wash. When he emerged from the bathroom without drying himself, water dripping all over the floor, he caught the slight look of irritation on Nandi’s face, but she held her mouth.

“No insinuations, Phila,” she said. “I’m just exploring your state of mind. You said it is not altered? Is it more like possession, trance?”

“No!”

Nandi paused in putting on her pantyhose. “Do you know about analeptic memory?” she asked.

“Not much, just description.”

“I’ve not studied it in depth either, but I know a little about it. Jung was interested in what he called ‘the collective unconscious’.”

“Yes.” Phila indicated for her to go on.

“Well, I read about a case in Scotland. This guy, his name was James Fraser, was a cartwright or some such. Anyway, it was just after the Second World War. Fraser had a recurring dream, which he told in convincing detail. In the dream he was a witness to this battle, I even remember its strange name, the Battle of Blàr na Léine. The manner with which he gave details convinced historians that he had been there, actually seen the fray. The problem was that this battle, which had been between the Frasers and some other clan, in which nearly all the Frasers were killed, occurred in 1544, centuries before James had been alive. His description of things like the clansmen’s dress, equipment, and methods of fighting could be verified only through specialised sources – sources that could not have been available to him at the time.”

“Umh!”

“Whatever you choose to call it, flood of ancestral memory, or analeptic memory, the thing seems to happen. Scientists say sometimes the exteroceptive stimulations, absorption of external stimuli, in other people, fail to perform or become too active.”

“Why?”

“No one is certain. But the absorption is a necessary process for maintaining normal waking consciousness. The altered state of mind is caused by levels above or below this level. You say you get visits from the historical figures you’re reading about?”

“Something like that.”

“Then this is my take on it. For some reason I think your concentration and absorption when you’re reading about these people causes these fluctuations in your stimuli, causing these altered states of consciousness. And that’s when you get these ‘visits’. Do you take any hallucinogenic? I mean, anything – say, Ecstasy?”

“I’ve never taken drugs. You know I am just an alcoholic.”

“I still feel we need to talk further, professionally.”

“You keep missing the point. I’m not treating this as a sickness. It’s something that has always happened in Xhosa history, especially during times of extreme pressure. It is what produced the Nxeles, Ntsikanas, Mqantsis, Mlanjenis and Nongqawuses of this world.”

“If you say so.”

“There you go with your know-it-all condescending occidental attitude. What if this is a normal thing in our tradition, how we deal with the pressure, by dipping into the parallel world of the River People, iminyanya? Is this not the essence of ukuthwasa? Have any of you psychologists bothered to study this thing closer? Funny thing is that you yourself once told me that Winston Churchill experienced a similar thing during the Second World War when England was under German bombardment. He called it his ‘Black Dog’. Of course everyone respected it and thought him unique because he was Churchill. Had he been African, black even, he would have been called voodoo crazy and superstitious, right?”

Nandi regarded Phila steadily. She put a hand on his arm. “Go home, Phila,” she said. “Go and bury your father.”

The River Tent is Broken

“THAT’S STRONG ENOUGH TO float an egg.”

Siya handed Phila a cup of black coffee and sat down opposite him at the kitchen table. He took a swipe of it. “Aah! Heaven.” The strength of the brew agreed with him. Since he’d arrived at the family house in Queenstown, they had been talking about everything except the death of their father. This made him feel implicated, but in what he had no idea. Something in his father’s body had burst. All he could think about was that the shit had hit the innards. Phila felt crude in thinking about it along those lines, but he was never of the euphemistic lot. He didn’t care because he felt whatever burst in his father was bobbing towards his own innards anyway. But that is not the kind of conversation you have with your sibling on the morning you are planning to see your dead parent at the mortuary.

“I was wonderfully amazed to see the apricot tree is still there!”

“Yep. And it still yields fruit in due season.”

Siya was usually taciturn so Phila tried not to read anything from her brief sentences. There were hanging issues neither of them was in a mood for at that moment. Besides, neither knew where to start, or what the point would be of plucking hanging issues instead of letting the fruit fall down to be manure, or poison. The Polish philosopher Leszek Kolakowski talked about the ‘law of the infinite’, saying that an infinite number of explanations can be found for any given event. Some clever professor whose lecture Phila had attended in Berlin connected this with what psychologists christened ‘hindsight bias’: the tendency to regard actual outcomes as more probable than alternatives. The whole thing hadn’t really made sense when Phila read it, but now he was either more gullible because he wanted to avoid thinking about his dead father, or else the bulb was getting some electricity. His hindsight bias was always in suspecting he could have done something to change the course of things had it not been for his proclivity to leave well alone. Could he have been more attentive to the needs of his girlfriend? Could he have suspended his moral judgement to save his firm, for ‘the greater good of all’? Could he have made time to visit his father and talk things out? Could he have, could he have…? What could he have?

Primo Levi survived the brutal torture of the Nazis in Auschwitz, and had spent most of the rest of his life writing against revenge and refusing to be a victim. Then he’d jumped off the third storey of a building to kill himself when he was sixty-seven years old – oddly enough, the same age as Phila’s father. Put your hindsight theory to that and shove it, he thought. We are a mystery mostly to ourselves. What we accept with our heads makes for our necessary fall when the heart has rejected.

Everything is falling, and I’m included in it, he thought as he looked at his sister’s beautiful face. Made him admit that his fat

her gave them good genes.

Just so we’re clear about things: no medically trained person dies of a perforated ulcer by accidental neglect. Even the ways by which we fall come from our agency, conscious or otherwise, was Phila’s last thought.

The following day they travelled to their father’s rural home, seventy kilometres east of their hometown. The burden of the hours came with Phila. It had been close to three decades since he had seen the place. He trained his eye on the passing villages, the sparse, abstract shoreline of brown and turquoise hutments against the lion’s mane coloured grass. The mountains, bleak and untamed, still possessed a haunted look. Progress and consumerism had caught up with the area since the change of government from the apartheid regime. Bridges had been built over rivers; electricity installed for those who could afford it; purified water coming out of installed communal taps, free of charge. Things were changing for the better, he thought, but what, he couldn’t help wondering, would Dr Samuel Johnson have had to say about it – Johnson had been of the opinion that change of governments makes no difference to the happiness of ordinary people.

The earth still heaved towards the craggy cliffs, building up to green mountains where the river snaked in a labyrinth to create the valleys where, for six generations now, his forefathers had lived and planted their fields. From there the road can take you no farther, what with the prince of the mountains, Lukhanji, standing in your way and casting its shadow over everything. The mountain sent water down the sedimentary donga, creating streams that acted as bloodline arteries for the valleys. This was where his father had hidden his defeated life, here among scrawny-looking sheep and an austere cluster of rondavel huts. This lonesome hill, with its echoes of the muffled screams of the dying river.

Traditionally, it was Phila’s home also.

It was evening when they arrived, the day before their father’s funeral, and the activity was already widespread. Bundles and bundles of wood lay around. A bull was being slaughtered at the kraal, because his father was a first-born, which traditionally mandates a bull falls with him. Pots of samp, cabbage and potatoes were boiling at the hearth. And the last containers zamarhewu were being brewed and distilled. Everyone had something to do but Phila. When he wanted to lend a hand he was directed away to something else, mostly some less arduous task. He became used to the dismissive gesture. “This is not for delicate hands, yezifundiswa.”

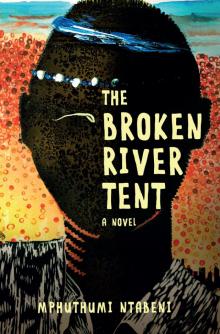

Broken River Tent

Broken River Tent