- Home

- Mphuthumi Ntabeni

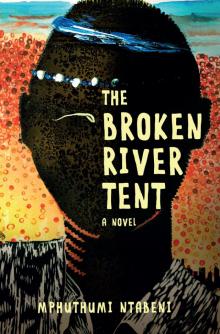

Broken River Tent Page 5

Broken River Tent Read online

Page 5

Being classed with the namby-pamby educated class irritated him. But he was clumsy in basic things like logging, keeping a straight line behind a cattle-drawn plough, or milking cows. He walked from kraal to shed, hearth to kitchen, pen to graveyard, looking for something to be useful at. No one required his help. His only usefulness was in driving a car or tractor to fetch the elderly. Whenever he met up with his elders Phila had a strange inclination to act more sombre than he actually felt in order to look for their commiseration. He felt he had to demonstrate to them the fact that he loved his father. Internally this made him feel like an impostor. Of course he felt loss for his father, vague as it might have been. He suspected it to be more about sentimentality, his tendency to idealise loss or absence. Absence does not get more permanent than death.

He walked past the graveyard, thinking how the Jewish culture was better in these situations. Everyone was allocated their own role to play. As children they would be obligated to visit the graves of their parents; to frequently recite prescribed memorial prayers at the graveside. Phila felt this prescribed mode of mourning ritualised loss better, giving it direction, perhaps even purpose.

He went on a gadabout riverward, to ponder things out. Standing on the river bank, in stilled attention, listening to the sounds of his childhood, remembering how he and his cousin used to trap crabs here when he was about seven, open their ‘purses’ to look for the coins they were told they contained. A line from TS Eliot’s The Fire Sermon trespassed to his mind:

The river’s tent is broken: the last fingers of leaf

Clutch and sink into the bank. The wind

Crosses the brown land, unheard. The nymphs are departed.

And there came his cousin, driving a cart pulled by two oxen, wearing gumboots, chaps on top of his dirty jeans and a tattered checked shirt, and with a gleeman song on his mouth. A suede hat sat precariously on his head. They greeted. Talked about days gone by. But the natural innocence of youth had been lost even between them, leaving behind awkward silences. His cousin was the one who knew all the cattle by name and colour, not just number like the rest of them. He was the one who knew what to do when the rains didn’t come to avoid the crops failing or the stock dying. He was the one who knew what his father thought in his last days as the ulcer bore into his innards. Phila knew in his heart of hearts that his cousin should be the one to inherit all that was left behind by his father. After all, according to the messiah, the meek inherit the earth.

“You remember, mzala, how we used to fish the rivers?” his cousin asked as he sat down, lighting his dagga pipe.

“I was just thinking about that. We used reed poles to tie the fishing lines. And no reel. I remember how once the pull slashed your palm …”

“Indeed!” His cousin extended his hand for Phila to examine. The scar was still there, smaller than Phila was imagining it in his head, but nasty all the same.

“What is happening to the river? Why is it dwindling, drying up?”

“They dammed it for water for the town folks,” his cousin answered without much concern. Phila, on the other hand, felt anger. They talked about when the dam was built by the apartheid regime with no consideration given to village people. “The fish of our youth died with the river,” his cousin said. As he got up to continue on his way with the cart, Phila wondered if this was one of the reasons black people were angry, burning and damaging things – because they were looking for their youth.

The day coiled like a spring in his mind. His father had told him the drive to swim upstream, for the spawning run, was always strongest when the fish sensed the dying light. After circling in the river bed, to avoid obstacles and rapids, they suddenly bunch up when the light goes down. His father, an amateur fisherman, had said all fishermen when they go to the river are in pursuit of their moment of art. It is an ancient tryst between them and the fish, when both are aiming to give a head-start to their spoor at the chow line, upstream. Explaining the difference between catadromous and anadromous fish, he had told Phila how the river left its identity on the scale map of the fish. That ichthyologists are able to study the conditions of the river from the scales of the fish who are born of it.

When they went hunting, and had to wait out the rain in the caves sometimes, his father explained the difference between stalagmites and stalactites to Phila, who busied himself with dreaming of ways to get out of the cave.

Then came the storm, the divorce, placing fate in the driving seat. But because Phila was born of the river that snaked the craggy mountains he couldn’t get rid of the river murmur on his skin, not even by the roaming of his roving mind. Stuck in that cave he traced his steps riverwards, heavy with speech, like shoal seeking to spawn upstream. But the river had dried out; only the willow branches waved. What now, Phila wondered, the stabbing shafts of the dying light on his mind. He plucked a stem of dry grass to chew and then laughed at himself: this was his father’s habit. We’re our father’s sons, he thought.

At last, his father found his art moment, in death. Because you can’t love anything without loss, and no one is ever entirely in charge of their own consciouness and genetic moves.

Tears tiptoed down Phila’s cheeks. He cupped his hands to cover his eyes, squinting to watch his cousin drive the spanned oxen up the hill, continuing with his gleeman’s song walking in lunging steps. Phila entertained the idea of hanging around a little, while he was still stranded, to clarify issues in his head, plant cabbages like the proverbial Hadrian, become one with his people, a hewer of wood and drawer of water. He imagined himself doing something constructive in the village, like building a school or a clinic, to etch the memory of his father on the rock. But when the money issue came into the picture he felt discouraged. Untangling himself from such thoughts, he took a better look at the view that had harnessed his father’s life. Again, he tried to see the nobility of living with a spirit of poverty hovering on one’s shoulders. It’s pride, damn stubborn pride masquerading as humility, he thought, no longer thinking about his father. He surveyed the wide domain where speeding winds crossed the lea. There’s a snake in the grass, he thought to himself. The truth is grounded in stronger pain, in groping the wound until the poison is drained out of it. Pain and consciousness cannot be separated, as the stoics saw it a long time ago. Phila was now also convinced.

The sun, low and big, sank with ill-placed drama behind the mountain brow. A trail of ashen clouds, like blooded fleece, bleated the pain of Ramah, Rachel weeping for her children. Sheep stood stupefied in the fields where women were threshing.

Phila didn’t really want to live chained by modern standards, but he did not need to look deeply within himself to realise he was too accustomed to modern comforts to ever give them up for frugal living and stoic values he hardly understood. From that realisation the spirit of his dissatisfaction rose. He ceased interrogating himself further and walked back, closely tied to the apron of his grief. No thinking, no thinking! We’re in mourning. Minute by minute the darkness settled on the hills whose shadows chained Phila’s cumulative memory. He understood now that grief was a last gift of love we unconditionally give our loved ones.

During the funeral Phila stood close to his paternal grandfather, so close he could see himself in his eighty-nine-year-old rheumy eyes. The bonding warmth between them no wreaths could define. When he noticed all the male members of his family had shaved their heads, Phila felt shame that he had not done so. Why had they not asked him to? They treated him differently. This had the effect of isolating him. His failure to shave might have been misinterpreted by the others as belittling his father’s death and lack of respect, but they were always cutting him some slack, viewing him as an anomaly.

It was an extremely cold day. Phila had never seen the mountain slopes in the area that white with snow. It felt like he was listening to the funeral proceedings in German.

Eulogies came thick and wide. Phila always felt this to be the worst part of African funerals: lengthy, irrelevant, t

urgid, sanitised hagiographic versions of the deceased. The situation was rescued by his father’s neighbour, a frail old man with a falcon-like face. With tingling sincerity in his voice, his undeceiving eyes spoke of old traditional wisdom and blunt dignity. His speech had the quality of biblical economy. Phila immediately adored the old man for trivialising the false sacramental gravity of other speakers; for being blithely indifferent to death. He could feel his own parasitic Augenblicksbeobachtungen awakening to translate the old man’s speech, spoken in Xhosa, in his mind. He jotted down now and then on the serviettes parts he did not want to forget from the speech; while translating it in Thucydidean mode inside his head. When he finally had it jotted down he was frustrated by how he had lost its natural bluff humour and living energy. Only those who still live with a carry-over detail of oral culture can manage such things, he thought, in excusing himself. The only thing he got right, he felt, was its pristine intensity:

“Today my soul is filled with heartbroken revolt against my own life. I do not know why we should be spared when our children are felled. To bury your child, as Mzoli [Phila’s father] was to me, is a harsh reality and cruel fate. [Stopped for a while to catch his composure.]

“Mzoli, you ‘feign-hell’. [Laughter lashed through the crowd. ‘Feign-hell’ was Phila’s father’s leitmotif whenever something went wrong. Hitherforth it became the harlequinade on the day of his interment. The old man stammered on with a slight lisp before continuing.]

“I don’t know who you think will turn my fields, sow my seeds and pluck my tares when you decide to join those fainéant you call your ancestors. All right then, Ndlovu, have it your way. One thing I know: the maggots will be at you tonight. We’re coming too, so don’t get too comfortable, occupying spaces of elders. It makes no difference that you go there first; we’re still your elders.

“Your departure shook our hearts but does not agonise us. Nobody osisimaphakade in this world. It did not happen to you what does not happen to others. You suffered the fate of all mortals. There’s no resisting death. It levels and calls all bluffs. I’m old as the hills; my hair is white like ewes on the fields, but yesterday I dug your grave with a spade on my own hands, against the protest of my family and friends who feared for my health. What do I need my health for if the likes of you are dead? Nothing made me more happy and proud as digging your grave. We’re even then, Ndlovu. Don’t you be asking for any favours when I get there where you sleep with those striplings you call ancestors.

“Your wordy and obsequious friends from town here say you were going to be a preacher. That’s bunkum. Iyilo like you. Still, you were a mast in our village. We’re the people who’ll feel the loss of your departure most. [He trained his eyes on the audience.]

“Allow me, people of my hearth, to lick my wounds in quiet. Nobody should drink this common crock more than a mouthful. It’s on its dregs already. Load every memory of him, wreaths if you wish; but now let us bury Mzoli and be done with it.

“We’re getting fewer by the day. Damn it! This land shall not see the likes of us again. May God give us the light of His wand in this death journey.” [He sat, deliberately slow.]

Phila really admired such hermetic eloquence.

The following day, he and his sister drove back to town. Phila had a headache. It was quiet in the car except for the fan blowing hot air and comforting odours. Soft showers, with occasional snow, fell with the memory of the departed. Cars, sliding, dancing and getting stuck in the snow, blocked their way now and then. Phila tried to strike up a conversation with Siya, the only non-talkative person he knew to be worse than him.

“The mountains and rivers have an ancient quiet stir that haunts those burdened with history or something.”

“Mhmm” was the only answer he got. He subsequently drifted to sleep as his sister drove.

‘I had a father, too, a chief, for that matter,’ said Maqoma from the back seat.

‘Before you start your monologue, please know that I’m very tired, and not in the mood for talking. Please! I’ve just buried my father. So if you don’t mind …’

‘I’m sorry. That was a little insensitive of me.’ He kept quiet for a while. Then, with whimsical stubbornness, he added, ‘I noticed you didn’t shed a tear for your father.’

‘And what is that supposed to mean?’ asked Phila in anger.

‘That you were not affected by his death in your depths?’

‘Give me a break.’

‘Your hero, Boethius, says the Roman emperor Nero refused to shed a tear for his beloved mother when she died.’

‘That’s because that mad fucker had her killed by drowning.’

‘Stabbed the belly which brought forth such a monster. We still hear her voice here screaming that she’s caught up in that permanent moment. My point though is that others have done worse than not crying for their parents. You’ve nothing to be ashamed of. I forced myself to break the calabash when my father, Ngqika, died, but it was not something coming from my heart. We had grown distant during his last years.’

‘Tears are not the only signs of grief.’

‘I know. You summoned me by other means, like desire to understand.’

‘You are my understanding? So far you have not been much help in that regard; if anything, you’re confounding my confusion.’

‘The year is not over yet.’

‘How I wish it were. The sooner we part ways, the better.’

‘You think?’

‘Okay, my understanding, tell me this. What happens to my father now?’

‘I’m not supposed to tell.’

‘Some understanding, you are.’ Phila resigned himself.

‘I’m here to make you understand things connected to this life alone, not those that go beyond.’

‘You impose yourself on my life, telling me you’re my understanding, only you can’t make me understand things I really want to know. Meantime I’m supposed to listen to you rant about your past?’

‘I was told to narrate my life experience to you, that’s all. I think it’s supposed to help you make better choices.’

‘Well, there hasn’t been much information so far, except for your long monologues. Excuse me, I’d really like to rest, the past week has been hectic for me.’

When they arrived in town, the only place Phila felt he was good for was a shebeen. The loud music screeched on his nerves, drowning his thoughts for a while, but he danced to it. After the fourth beer his head started feeling light, but lacked the rush vitality alcohol usually gave him. If anything it reinforced the dull sense of things. He took a seat in the lounge, not in a mood to socialise with people around, who kept giving him probing glances. Empty beer bottles thickened before him. He felt the main theme of his life was obscured in the details of his father’s but didn’t know how to retrieve them. He was dismayed by his suffocating grief.

It was after two in the morning when Phila walked home. Lying on his back on his bed he gazed up at the ceiling in meditative integrity of darkness, considering the light and a glint of anger he didn’t quite understand. After a while Maqoma’s voice reached him through the dark.

‘In any case, Gcaleka and Rharhabe were twin brothers of the last king, Phalo, of the united Xhosa nation; Rharhabe being …’

Phila tried to close his eyes and ears, but to his dismay discovered he could still clearly hear and see Maqoma.

‘When iMbokotho was broken, the sons of Phalo fought from their mother’s womb. We saw bulls of the same byre gore each other, opening wide the gates for the enemies to flood in. When he got older Rharhabe crossed tributaries, like Izeli River, near the drift, where he killed inyathi. To show he harboured no ill intent to his brother he sent its breast and leg to the great place as a tribute. His brother Gcaleka accepted the gesture, although they had recently been in conflict. The gesture meant Rharhabe was subjecting himself to the paramountcy of Gcaleka. Thereafter, Rharhabe called that river Nyathi River.’

‘So that is why it

is called Buffalo River?’ Phila couldn’t contain his interest.

‘The area was still too close to Gcaleka so Rharhabe continued roving.’

‘You know they’ve named that whole region Buffalo City now?’ Phila was finding renewed interest in the talk.

‘Yes, I noticed. Nyathi would have been better, but Buffalo will do. Rharhabe settled for a while at Amabele, near where the white people established their town.’

‘Stutterheim?’

There was silence and heavy breathing. ‘Are you still with me?’ Maqoma enquired.

‘Yes! But my head is starting to rill.’

‘Do you know Qumrha?’

‘Why would I not know Qumrha?’

‘I couldn’t find it on your map when I looked for it.’

‘That’s because it is called Komga now.’

‘Why is that?’ Maqoma looked puzzled.

‘Because white people couldn’t click, what else? The same has happened with Ingqurha, it is now called Coega.’

‘You don’t say. Their takeover of this country is complete.’ Maqoma’s skin wrinkled like leather when he was shocked or laughing.

‘Guess who we’ve to thank for that?’

‘Are you implying that we sold the country to white people?’

‘I’m not implying your lot handed it over in a hot plate. While you were busy fighting each other, they stole the land from under your noses.’

‘You don’t know what we did to resist and keep the Xhosa nation united. You must not talk about things you’ve little understanding of.’

‘As luck will have it, I have you to be my understanding, which just makes things worse.’

Broken River Tent

Broken River Tent